The Runic Cosmogram

Introduction to the Nordic Runes

Of late, the Norse Runes have been calling to me, nagging at me. It is a divinatory system I have not worked with and up until recently knew very little about. Also it should be said right away, it is something quite beyond a divinatory system.

The Runes come to us via ancient Norse mythos and culture and have endured as a recognisable form of divination. Much like Tarot and Astrology, the Runes have been reduced by misuse and Instagram spirituality to a form of hacky fortune-telling and parlour-trick level esoterica, denuded of their original power and dignity.

Divination is the way we can read signs, symbols, patterns and other cues to divine the deeper patterns of intelligibility and causal principles of the cosmos and of life. The Runes are a philosophical and initiatory language that encodes how reality moves, differentiates, and coheres.

Each runic figure or stave, is an archetypal lens onto or into a fundamental enduring or causal principle and together they form a map of the relationship between vitality, consciousness, and Law.

Unlike Tarot, the Runes were used in a talismanic and invocational sense, an active technology rather than a reflective one. This is to say that they are not meants to be laid out only to read or divine the unfolding of fate, but carved, sung, and inscribed to shape the unfolding of Fate.

Each rune was understood as a living power, a sound-form through which the cosmos is brought to order and by which order is brought into being. To inscribe a rune was to invoke its presence, to open a channel for its force to move through the world and through oneself. The enscriber enters into a covenant with the greater spheres of order via the rune’s essential power: intentionality, breath, and making a mark, awakened its power, binding meaning to matter. This is why runes were cut into weapons, ships, and stones, worn as amulets, or painted on ritual objects.

If Tarot describes a field of archetypal relationship, then the Runes exist as keys to that field. They are the active counterpart to contemplation, the grammar of manifestation itself. To work with them is to engage this aspect of Logos directly: to speak the ancient language through which will expressed as word can shape emergent reality. Working with Tarot helps us to deepen and refine our archetypal and symbolic language and internal predictive models. Working with the Runes, by contrast can initiate and activate those same patterns.

Given the profound insights I gleaned and am now able to share through the deep etymological, archetypal and noetic analysis I stepped through with the Major Arcana and which resulted in The Loom, I feel called to explore the runes to the same or similar level of Depth.

The intentionality driving this thread of the Hermetica Reiterated project, is to see what depth and insight can be brought to light by approaching the Runes through the most discerning synthesis of academic, linguistic, and esoteric understanding available. And then, as I did with the Tarot, to sit with each symbol in contemplation and let its archetype and etymology speak directly to Nous.

This is not a study of folklore or a verbatim repetition of what one will find elsewhere on the internet, and is also not an attempt to kindle any cultural fetish. Each Rune will be treated as a living ideogram of cosmic law, a precise articulation of Logos in symbolic form (Mythos). I intend to trace its linguistic root, its mythic resonance, and its archetypal tone, and then allow what unfolds to reveal the same Logos that speaks through all true symbolic languages.

Just as The Loom revealed the Tarot as a map of the psyche’s dialogue with Logos and Language and Mythos, I am trusting that this work will go some way to restore them to the dignity of their original register.

My intuition, which remains to be founded or debunked, is that the Runes comprise a contemplative and initiatory grammar through which Nous may apprehend the deep resonance and coherence of fundamental ordering principles or archē, of reality.

The Arrangement of The Runes

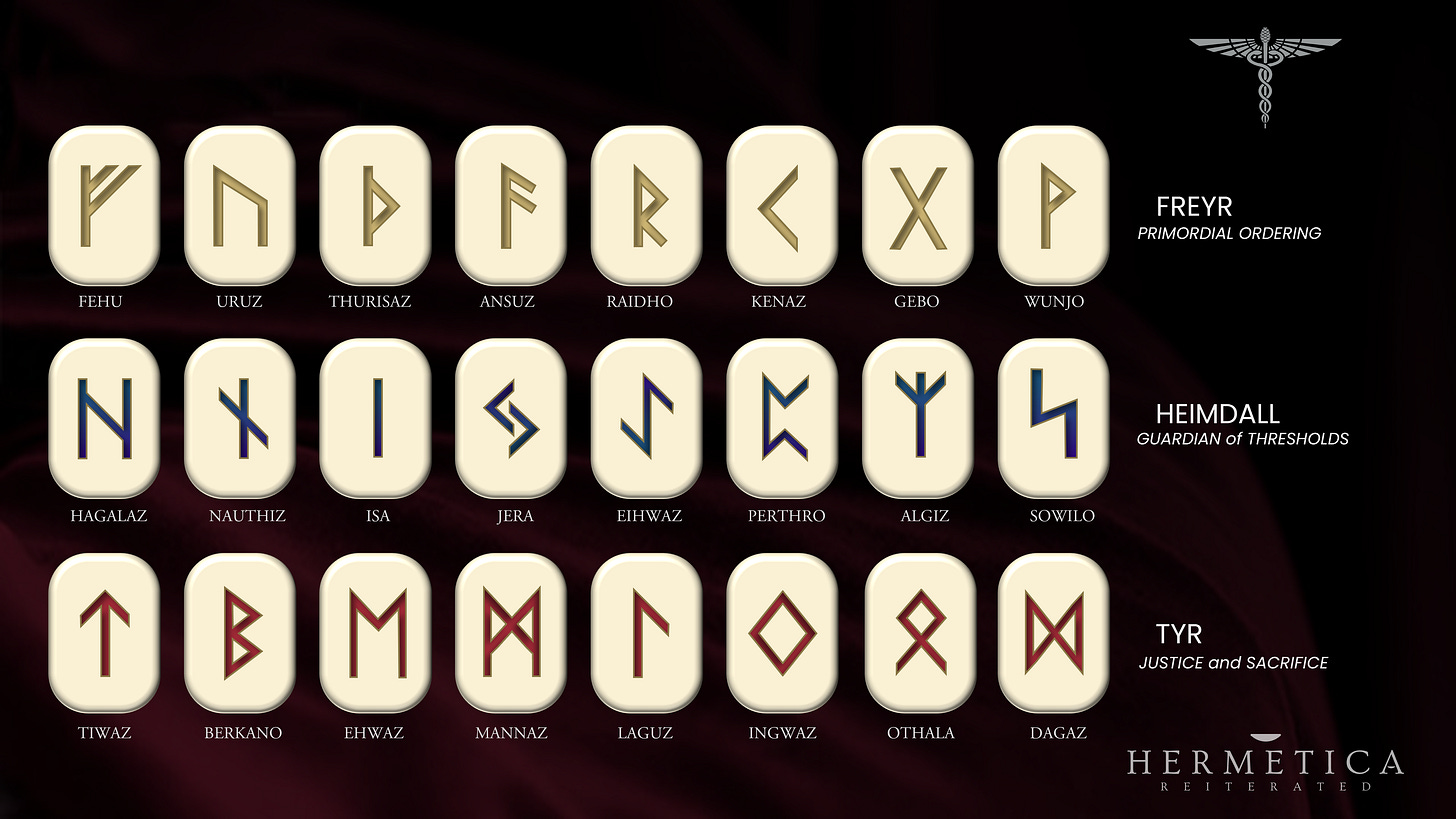

The Runes are said to have a natural order, a sequence that is not arbitrary but inherent to their cosmological logic. This order, known as the Elder Futhark, consists of twenty-four staves arranged in three ættir of eight. Each ætt expresses a distinct phase in the movement of being.

This structure reflects the tripartite order of Norse cosmology and mirrors the stages of existence itself. The colours assigned to each family or ætt is symbolic and intentional.

The first, Freyr’s ætt, concerns the generative and vital forces of life, wealth, strength, growth, and harmony. (Green & Gold.)

The second, Heimdall’s ætt, embodies initiation and transformation, the trials, constraints, and revelations through which consciousness is tempered. (Indigo and Ice Blue.)

The third, Tyr’s ætt, expresses integration and sovereignty, the realisation of law, partnership, wisdom, and legacy. (Crimson & Silver.)

Together they form a complete system of cosmological principles, describing the movement of being from manifestation, through ordeal, to realisation.

A deeper archetypal understanding of each of the Gods and their archetypal functions in the cosmology are necessary to appreciate the arrangement:

FREYR

The Generative Principle, Lord of Fertility, Reciprocity, and the Living Order of Life

Freyr belongs to a pantheon of gods older than the Æsir, known as the Vanir. The Vanir are deities of fertility, vitality, and natural law, representing the self-renewing intelligence of the living world. They are the embodiment of immanent order, the power that arises within nature rather than above it. After the war between the Æsir and the Vanir, a truce was made, and members of each pantheon were exchanged to seal the peace. Freyr, his sister Freyja, and their father Njörðr came to dwell among the Æsir, bringing with them the wisdom of cycles, fecundity, and balance. Through this union, the Norse cosmology acknowledges that cosmic order requires both the transcendent principle of the Æsir and the immanent principle of the Vanir.

Freyr’s ætt, which opens the sequence of the Runes, therefore begins with the forces of generation, abundance, and reciprocity, expressing the fertility of being itself before consciousness enters the crucible of transformation.

HEIMDALL

The Sentinel of Consciousness, Guardian of Thresholds, and Herald of Awakening

Heimdall is the bright watcher who stands at the bridge between worlds, guarding the boundaries of Ásgarðr and Midgarðr. Born of nine mothers, each a wave-maiden of the sea, he is a being of pure liminality, his origin itself a synthesis of the elemental powers that shape existence. Heimdall embodies perception refined to its highest state: he can hear the grass grow and see for hundreds of leagues. In myth, he sounds the Gjallarhorn at the dawn of Ragnarök, awakening gods and mortals alike to the final reckoning. Archetypally, Heimdall represents the initiatory force that calls consciousness across its thresholds of transformation. He presides over ordeal, awakening, and revelation, the processes by which perception is tested, expanded, and made clear.

His ætt governs the middle order of the Runes, the crucible in which the raw vitality of life undergoes challenge and refinement, preparing the soul for the higher integration of law and wisdom.

TYR

The Principle of Sovereignty, Sacrifice, and Divine Law

Tyr is the oldest of the gods and the embodiment of right order. Once a sky god of justice and cosmic balance, his authority predates even Odin’s. In the age of the Æsir he becomes the exemplar of moral courage, remembered as the one who placed his hand in the mouth of the wolf Fenrir so that the beast might be bound and the world preserved. In this act of self-offering, he establishes the supreme principle that true authority is sustained not by dominance but by integrity and sacrifice. Archetypally, Tyr governs the realm of justice, law, duty, and conscious will aligned with higher necessity. He represents the mature realisation of divine intelligence, where action and order become one.

His ætt completes the runic sequence, embodying the culmination of the generative and initiatory forces in the full integration of wisdom, responsibility, and legacy, the sovereign equilibrium of Reason within creation.

The Twenty Four Runes

Over the next many weeks, I will be exploring each of these in turn, but here are the current names, symbols and basic meaning of each rune.

Fehu ᚠ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic fehu, “cattle, movable property, wealth”, root of Old English feoh and modern “fee”.

Synthesis of meaning: Mobile wealth and life force, the power that flows through resources, livelihood, fertility and exchange. Concerns gain, loss, generosity, obligation and the ethical use of what you hold in trust.

See Full Article: Runes: Fehu

Uruz ᚢ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic ūruz, “aurochs, wild ox”.

Synthesis of meaning: Raw, untamed vitality and bodily strength, the deep reserves of will, endurance and instinct. It signals primal vigor, health, challenge, and the necessity to shape or channel raw power rather than let it stampede.

Thurisaz ᚦ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic þurisaz, “giant, troll, hostile powerful being”.

Synthesis of meaning: Threshold pressure, breaking forces, and the ambiguous power of disruption. It is conflict, shock, and also the necessary friction that protects boundaries and breaks stagnation. Divinatory work reads whether this pressure is to be withstood, redirected, or invoked consciously.

Ansuz ᚨ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic ansuz, “god, one of the Aesir”, related to inspired speech and breath.

Synthesis of meaning: Inspired communication, insight carried on breath, the inbreaking of signal from a higher order of mind. It speaks to language, teaching, omens, mentorship and the integrity or corruption of the spoken word.

Raidho ᚱ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic raidō, “ride, riding”, related to “road, raid, ride”.

Synthesis of meaning: Right movement, journeying, process and timing. It is the rhythm of events, the difference between wandering and pilgrimage, and the alignment of inner intention with outer route and schedule.

Kenaz ᚲ

(historically Kaunan)

Etymology: Proto-Germanic kaunan, “ulcer, boil”, later associated with Old English cēn, “torch”.

Synthesis of meaning: Concentrated fire, the inner flame that burns away what is diseased and illuminates what is true. Linked to craft, learning, creative insight, and also to the pain of necessary cauterisation or exposure.

Gebo ᚷ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic gebō, “gift”, from a root associated with giving.

Synthesis of meaning: Reciprocal exchange, bonds formed by offering and obligation. It speaks to partnership, contracts, generosity, vows and the balance of mutual benefit, including the hidden cost of imbalanced giving or taking.

Wunjo ᚹ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic wunjō, “joy, delight”.

Synthesis of meaning: Cohesive happiness, harmony and shared goodwill. Not simple pleasure but the satisfaction of alignment between self, group and circumstance. It highlights morale, belonging and the relief when tension resolves into ‘right relationship’.

Hagalaz ᚺ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic hagallaz, “hail”.

Synthesis of meaning: Sudden disruptive events, external shocks that break patterns. Like hail, it damages but also feeds the soil and clears the air. It signals storms, unexpected reversals and the deeper reconfiguration they enforce.

Nauthiz ᚾ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic nauthiz or nēþiz, “need, necessity, compulsion”.

Synthesis of meaning: Constraint, lack, pressure from necessity. It focuses attention on what is missing, on hardship that tempers character, and on the discipline or creative workaround required when resources and options are limited.

Isa ᛁ

Etymology: Proto Germanic īsą, “ice”.

Synthesis of meaning: Stillness, stasis, hardening. It freezes motion, clarifies edges, preserves or blocks. It can mean patience, focus and containment, or conversely, emotional coldness, rigidity and deadlock that must eventually thaw.

Jera ᛃ

Etymology: Proto Germanic jērą, “year, harvest season”.

Synthesis of meaning: Cycles, seasons and earned fruition. It emphasises cause and effect over time, the turn of the year, and rewards that arrive in due course rather than on demand. It is slow, cumulative justice in the field of effort.

Eihwaz ᛇ

Etymology: Probably Proto-Germanic īhaz or eihwaz, “yew tree”.

Synthesis of meaning: The axis of endurance, death and renewal. Yew is a graveyard tree and also extremely long-lived. The rune speaks to resilience, initiation through ordeal, spine and backbone, and the capacity to stand firm between worlds.

Perthro ᛈ

Etymology: Unclear; commonly linked to a word for “lot cup, dice box, casting vessel”.

Synthesis of meaning: Hidden pattern, chance, mystery and the womb of becoming. It governs gambling, divination and the unknown configuration of causes now ripening into events. It points to what is concealed, gestating or decided by draws you cannot fully control.

Algiz (also Elhaz) ᛉ

Etymology: Possibly Proto-Germanic algiz or elhaz, linked to “elk”, but debated.

Synthesis of meaning: Protection, reach and alertness. Often seen as an antler or uplifted hand. It marks sacred enclosure and heightened awareness, the instinct to guard, defend and extend perception into subtle threat before it arrives.

Sowilo ᛋ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic sōwilō or sæwelō, “sun”.

Synthesis of meaning: Solar clarity, success and the organising force of conscious will. It illuminates, integrates and energises. It relates to victory, recognition, health of spirit and the burning away of confusion, but also the risks of egoic glare.

Tiwaz ᛏ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic Tīwaz, name of the god Týr, from PIE deywos, “god, shining one”.

Synthesis of meaning: Law, honour, sacrifice and principled action. It is the blade of justice, the willingness to give up something vital for a higher order of right. It often marks conflict resolved through fairness, leadership and alignment with a binding truth.

Berkano ᛒ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic berkanō, “birch tree”.

Synthesis of meaning: Birth, nurturing growth, shelter and rebirth. Birch is a pioneer tree; it is resilient, fast-growing, and able to establish itself in poor or barren soil where other trees cannot yet thrive. Its presence restores fertility and stability to the land, creating the conditions for richer ecosystems to follow. The rune speaks to maternal care, recovery, new projects and healing environments, as well as the need to clear old undergrowth for fresh life.

Ehwaz ᛖ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic ehwaz, “horse”.

Synthesis of meaning: Partnership, trust and coordinated movement. Horse and rider function as one. The rune reflects cooperation, teamwork, vehicles and transitions, along with loyalty and the need for mutual confidence between partners.

Mannaz ᛗ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic mannaz, “person, human being”.

Synthesis of meaning: Human consciousness, selfhood and the social mind. It is the question of what it is to be a person within a collective, including roles, identity, projections and the interplay between individual dignity and communal structure.

Laguz ᛚ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic laguz or lahwaz, “water, lake, sea”.

Synthesis of meaning: Flow, intuition, emotion and the unconscious. It is immersion, tide and the nonlinear currents underneath rational planning. It can signify psychic sensitivity, dreams, longing, and also confusion or overwhelm when boundaries dissolve.

Ingwaz ᛜ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic Ingwaz, the god Ing or Yngvi, associated with a fertile deity akin to Freyr.

Synthesis of meaning: Seed state, contained potency and quiet gestation. It represents completion that is folded inward, preparation for emergence, fertility, and the closing of a phase so that another can be conceived in protected space.

Dagaz ᛞ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic dagaz, “day”.

Synthesis of meaning: Breakthrough, dawn, liminal transformation at the turning of light. It is the moment of irreversible shift in perception or situation, often sudden clarity, revelation or the culmination of a long unseen buildup.

Othala ᛟ

Etymology: Proto-Germanic ōþala or ōþila, “ancestral land, inherited estate”.

Synthesis of meaning: Ancestry, heritage, belonging and the structures that persist beyond one lifetime. It concerns home, lineage, cultural patterning, inherited blessings and burdens, and the question of what legacy you will, in turn, leave behind.

The Mythic Origin of The Runes

According to the cosmogony of Norse mythos, the Runes are not inventions of gods or men but intrinsic features of creation itself. They come into being as the cosmos takes shape from the body of Ymir, forming the hidden geometry through which order arises from chaos. The Runes are the primordial signatures of law, vibration, and relationship—the means by which the unmanifest becomes structured and intelligible. They lie beneath the roots of Yggdrasil, within the Well of Fate, as the very grammar of existence, waiting to be perceived by any consciousness capable of self-sacrifice and understanding.

In this mythic context, we encounter the existence of the Runes at a point where the Pantheon of gods have been established, the giants have been defeated, the worlds set in their places, and time itself has begun to move toward its destined end. The gods rule from Asgard, but they rule within limits: the Norns weave the threads of all things, and even the gods are bound by the pattern they spin. It is this realisation that drives the All-Father Odin to seek the Runes.

The understanding intimated to the listener or reader of the sagas is that power without knowledge can only be temporary, and that no act of will can escape the laws that sustain and undo creation. Many of the stories of Odin are about his quest to discover the hidden principles beneath Fate itself, which are codified into words like Wisdom and Knowledge, and the ability to ‘See what is’.

In one such story, Odin sacrifices himself to himself, to this quest, and pierced in the side by his spear, he hangs on Yggdrasil, the world tree, for nine days and nine nights in order to gain knowledge of other worlds to obtain the wisdom of the Runes. The sacrifice was necessary because the Runes would not reveal themselves without it—nothing for nothing—something must be given or endured to obtain something else of meaning.

In this tradition, the Runes are not considered ordinary letters of the kind used to communicate everyday matters in. They are the twenty-four sacred letters that were a part of the world, not crafted by men or gods, but came into being as creation and life unfolded, and whose knowledge granted the user mastery over the forces and forms of creation.

At the bottom of the great world tree dwell the Norns, the three sisters of Fate, whose names were Urd, “what has been”, Verdandi, “what is becoming” and Skuld, “what shall be”. One of the sisters, Urd, is the keeper of the fathomless well of Fate.

After the ninth night of hanging on the world tree, at the border between life and death, all the while peering into the depth of the well, the Runes at last revealed their secret forms to Odin, as well as the secrets that lie within them. Having fixed this knowledge in his formidable memory, Odin concluded his trial with a great cry of exultation.

Having been initiated into the mysteries of the runes, Odin recounted:

Then I was fertilized and became wise;

I truly grew and thrived.

From a word to a word I was led to a word,

From a work to a work I was led to a work.

“From a word to a word” denotes the way we build language and memory (in a tree).

In another story, Odin sacrificed his own eye, casting it into the well of Mimir, guarded by his primordial uncle. Mimir was known for his wisdom, the source of which was yet another deep well at the root of Yggdrasil.

When Odin asked for a drink, he was challenged with the notion again that for something exceptional to be gained, something valuable had to be given. In response, Odin tore out his eye and cast it into the well, after which he was granted a drink, through which he gained knowledge.

Ever after, Odin was called “One-eyed” for one of his eyes remained in the bottom of Mimir’s well, looking into the impenetrable dark where the secret knowledge of the world is found.

The notion of sacrifice, particularly in its ordinary and everyday sense, is a constant across the shamanic and animist traditions of the world. It marks the willingness to give up comfort, certainty, or safety in order to cross a threshold into deeper perception. Enduring liminality, that is, the in between, whether paradigmatically or socially, appears to be a necessary condition for such insight.

The Runes are the revelation of that search; language of the deep, integral order by which all subsequent orders and contexts exist via emergence and coherence.

Reference Sources

To anchor this inquiry in credible and discerning sources, this study draws primarily from Edred Thorsson, Diana Paxson, Nigel Pennick, and Jan Fries, each representing a distinct but complementary interpretive lineage within contemporary runic scholarship.

Of all the available commentaries and books, I chose these four voices with discernment because they each stand on the narrow bridge between scholarship and what appears to be some genuine initiatory understanding. They are neither rigidly academic nor uncritically mystical. This, for me, is key.

Thorsson provides the most systematic reconstruction of the Runes as an initiatory and magical system rooted in pre-Christian Germanic cosmology.

Paxson brings a disciplined blend of academic, spiritual, and experiential insight, restoring the Runes as a living language of practice and relationship rather than superstition.

Pennick situates the Runes within the rhythms of nature, time, and cosmological order, elucidating their connection to the cycles that structure being itself.

Fries approaches the Runes through the experiential and shamanic lens; treating each stave as a current of raw consciousness and embodied power.

Together, these voices establish something of a rigorous yet intuitive framework, balancing etymological and anthropolical context with integrity with metaphysical depth. This allows me to get a sense on their insights and thereby deepen my own conversation with the Runes in a way that honour the animistic and hermetic sensibilities I apply as the foundation of my reasoning and meaning making.

The fellow student should appreciate well that while I consider the insights and perspectives of these voices, I rely ultimately on my own knowledge and understanding of causal principles (Logos) and my own depth of archetypal language (Mythos) gleaned from the work with Tarot and my depth of study and practice of other esoteric frameworks.